Defense and governmental demand for unmanned aerial systems (UAS) is robust, especially in specialized mission systems, and commercial demand is unprecedented. Large corporations are aggressively moving to integrate UAS into their business operations, if only to keep pace with growing industry adoption rates. But the biggest driver is the consumer market. Manufacturers of small, hobbyist drones – UAS weighing a few ounces to 55 lb – are determinedly fostering the belief, in the marketplace and on Capitol Hill, that unmanned aircraft have real uses in everyday business operations.

Defense and governmental demand for unmanned aerial systems (UAS) is robust, especially in specialized mission systems, and commercial demand is unprecedented. Large corporations are aggressively moving to integrate UAS into their business operations, if only to keep pace with growing industry adoption rates. But the biggest driver is the consumer market. Manufacturers of small, hobbyist drones – UAS weighing a few ounces to 55 lb – are determinedly fostering the belief, in the marketplace and on Capitol Hill, that unmanned aircraft have real uses in everyday business operations.

The ease of use and accessible prices of hobbyist UAS have brought urgency to the issue. Imagery produced by these toy drones is captivating. That it can be collected by children at the controls gives the public a false sense of safety. Hobbyist UAS are not always benign, and they must never be allowed to threaten commercial and military airspace. Limiting this threat is becoming the most important challenge facing the Federal Aviation Administration (FAA).

More than a toy

Public and commercial customers commonly see no difference between hobby-shop drones and small UAS built for professional applications. The advanced autopilot capabilities of toy drones have created the perception that they are fitted with aerospace-grade avionics, even though most of their autopilot systems are derivations of video game and smart phone technology. Transponders, Automatic Dependent Surveillance-Broadcast (ADS-B) In/Out, command and control radio links, and aviation radios – among the most basic aerospace grade avionics packages – are seldom found in toy drones easily purchased at big box stores, online, or at a local mall.

The reality is that most small, consumer-market drones are not designed within a standard deviation of aerospace design standards, much less with airworthiness in mind. They require no significant training to operate, yet they could cause catastrophic damage in a collision with a manned aircraft in flight. Nor are these toys insurable in the same manner as unmanned aircraft, leaving potentially significant gaps in coverage for both operators and bystanders on the ground or in the air.

The reality is that most small, consumer-market drones are not designed within a standard deviation of aerospace design standards, much less with airworthiness in mind. They require no significant training to operate, yet they could cause catastrophic damage in a collision with a manned aircraft in flight. Nor are these toys insurable in the same manner as unmanned aircraft, leaving potentially significant gaps in coverage for both operators and bystanders on the ground or in the air.

Why type certification?

Whether they are mere toys or vehicles designed for commercial applications, unmanned aircraft systems are aircraft. To fly an aircraft in the U.S. National Airspace System requires FAA airworthiness certification and operating authorization.

The FAA type certification process is a proven method of obtaining explicit FAA operational authorization for the integration of new technology. Type certification achieves regulatory compliance while eliminating uncertainty in liability, training, operational efficiency, and total cost of ownership. Type certification is the only current means to achieve authorization for remote, beyond line-of-sight, and over-the-horizon operation of unmanned aircraft. The FAA’s type certification process is complex, but ultimately the most rational approach to ensuring the American public’s safety in the air and on the ground.

Meeting needs

Aero Kinetics’ unmanned systems business was born to fill the gap created by the success of toy drones and the need for professional level UAS. Commercial and governmental customers see the speed of ideation in toy drones awakening people to the potential uses for airborne robotics. Flying a toy drone as a technology demonstrator leaves them wanting to integrate airborne robotics into daily operations and the desire to scale up – perhaps 4,300 units across the continental U.S. and 23,000 units globally. But these customers need explicit FAA operational authority, and they need insurance, service, and support.

Hobbyist UAS cannot meet these needs, and corporate clients cannot and will not risk flying a toy drone over an urban environment or near manned aircraft. The inability to fly in these environments eliminates about two-thirds of the proposed uses for UAS – package delivery, aerial photography, or utility infrastructure monitoring.

While Aero Kinetics was the first to file for type certification for a multi-rotor unmanned aircraft, we firmly believe that it will take an entire industry to meet the future demand for these systems. The stakes are nothing less than ensuring the public’s safety and the integrity of the U.S. National Airspace System; indeed, the security of airspace worldwide.

Design opportunities

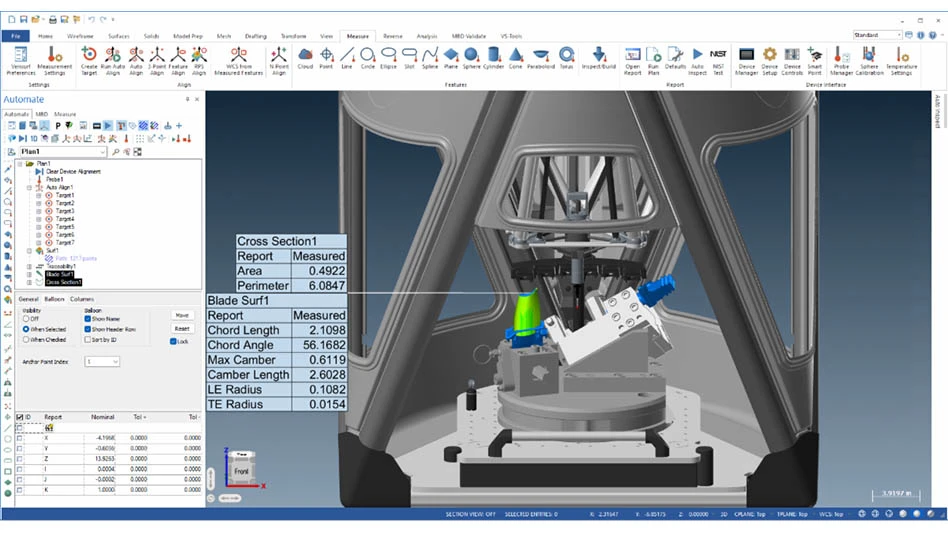

The only aspect of the UAS industry that remains constant is the coefficient of change. Sensors, hardware, software, design specifications, vendor supply chains, regulations, operation concepts, and client requirements are all in flux. Technical obsolescence of sub-systems and components is certain. UAS must be capable of rapidly incorporating new features, sub-systems, and components or risk becoming instantly obsolete. To be successful, it is crucial to implement a strategy that focuses the design process on user needs and business objectives and encourages information sharing across work groups and teams – whether internal, external, or the FAA.

The UAS industry is one of the few aerospace sectors not limited to traditional manufacturing practices. Because we do not have humans on board, we can explore new structural designs, organic geometries, and complex substructures that may someday transition to manned aircraft. Additive manufacturing in metals and engineered materials provide the ability to iterate and prototype at speeds never before possible and creates a true just-in-time supply chain. Design changes can be tested within hours of completion. In 2014, Aero Kinetics was producing a new and complete prototype unmanned aircraft every 40 days.

How can we manage time so that engineers and technologists can succeed? Given the coefficient of change, we must orient design, engineering, prototyping, quality, certification, production, and support processes to allow for interoperable systems thinking, and reduce wasted time and energy. Engineers, technologists, business analysts, and everyone else on the team must be focused on the most-important things, and quickly process the observe, orient, decide, and act (OODA) loop.

Reducing uncertainty

The largest challenge our industry faces is uncertainty – in customer and potential regulatory requirements, and in how unmanned aircraft will be used in the future.

The FAA type certification process is a beacon in this sea of uncertainty. It is available to the industry now, and has been proven capable of providing for the public safety. Customers know how they will be able to operate an FAA type-certified aircraft, and predict the cost of integrating UAS into their everyday operations. Such certainty is invaluable for all stakeholders.

The FAA may elect to publish an alternative path to certification, such as proposed Part 107, which addresses requirements for operators wishing to fly small UAS for non-recreational purposes such as real-estate photography, precision agriculture, media coverage, and law enforcement. Currently, the proposed Part 107 flight rules require an aircraft registration for each machine, but an airworthiness certification would not be required. We believe that a dual path is acceptable, as long as airworthiness certifications are required to provide for the public’s safety.

Aero Kinetics

www.aerokinetics.com

About the author: W. Hulsey Smith is chairman and CEO of Aero Kinetics. He can be reached at hulsey.smith@aerokinetics.com.

Read the white paper, “The Real Consequences of Flying Toy Drones in the National Airspace System” at http://goo.gl/DqvgDE.

Explore the November December 2015 Issue

Check out more from this issue and find your next story to read.

Latest from Aerospace Manufacturing and Design

- Demystifying Controlled Unclassified Information (CUI)

- Simplify your shop floor operations while ensuring quality parts

- Happy Independence Day - July 4th

- Bombardier receives firm order for 50 Challenger, Global jets

- Automatic miter bandsaw

- SAS orders 45 Embraer E2 jets with options for 10 more

- Height measuring instrument

- Shopfloor Connectivity Roundtable with Renishaw & SMW Autoblok